Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

How Do Districts Respond to Charter Schools?

Ever wonder if the growth of charter schools drives a school district to alter their own model? Recent evidence suggests that not only do the largest districts respond to charter school expansion, but they respond to it more constructively than in the past.

Marc J. Holley of the Walton Family Foundation, with the help of two research fellows, Anna J. Egalite and Martin F. Lueken, recently released a study on district responses to charter schools and how responses differed across districts. They only studied 12 districts, which might at first seem too narrow of a sampling, but it makes sense when one considers that they were limiting the study to specific criteria: 1) at least 60% minority and low-income, 2) minimum of 6% charter student saturation, which is the number of students in charters that can be expected to draw a response from the district according to prevailing research, and 3) ranging geographic options, which came to three districts each in the Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, and West.

They discovered that every single one of the districts they studied had some kind of response to the growth of charter schools. Given how palpable charter awareness is in these districts, they set about to determine just what kind of response they had.

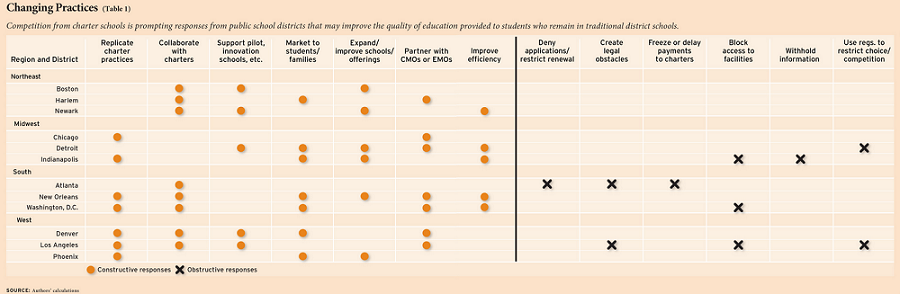

As it turns out, there were two primary kinds of response, Constructive vs. Obstructive, with several specific methods employed by the respective district in its response.

The great news is that most district responses were Constructive, which the authors say is a significant departure from the responses they saw earlier in the school choice movement (mainly throughout the 1990s and early 2000s).

The methods of their constructive response are listed below (in descending order of frequency – out of 12):

- Cooperation and collaboration (8)

- Partnerships with successful CMOs and EMOs (7)

- Replication of successful charter school practices and policies (7)

- Increased marketing of special district services (7)

- Expanding/improving district schools, programs, curriculum, etc. (6)

- Improving financial efficiency (5)

- Supporting semi-autonomous charter-like schools (5)

The first and most frequent method of constructive response was “cooperation and collaboration,” which can be broadly interpreted. Any modicum of cooperation could reasonably be construed as falling into this category, even if the district is required to do so by law. With this in mind, the fact that 8 of the 12 districts exhibited “cooperation and collaboration” is not too surprising.

What we at American School Choice would like to see are more of the methods that follow. For instance, the whole concept of market-based education reform centers around the increased efficiency that is inevitably created by the market forces of charter school competition. We want public districts to borrow ideas from charter schools (#3), advertise their market niches (#4), improve their models (#5), streamline their budgets (#6), and do anything else they can to try and win back “customers,” i.e. the parents and their students. Charter schools should be driving districts to be better, not driving districts into resistance.

Still, resistance is a very real thing in this movement, and the authors found plenty of examples of obstructive responses. They are listed below (in descending order of frequency – out of 12).

- Blocking access to public buildings (3)

- Creating legal obstacles to charter schools (2)

- Using regulations to restrict choice or interfere with competition (2)

- Freezing or delaying payments to charter schools (1)

- Withholding information from charter schools (1)

- Excessively denying applications or restrict renewal (1)

The two districts that created the most obstacles for charter growth and competition were Atlanta and, surprisingly, Los Angeles. Each used three tactics to limit charters, while Indianapolis came in behind them by utilizing two obstructionist methods. Detroit and Washington, D.C. both used one obstructionist method each.

Blocking access to buildings is a common obstruction; even if a board obtains a charter from an authorizer, they can’t open a school at all without a building (except for virtual programs). However, blocking facilities funding is also a major obstacle, and some states don’t even allow capital outlay funding. Do the districts get blamed for this, or is this in a separate category outside the scope of this study?

In fact, this brings up the one glaring omission in the study. What about the obstructionist responses used by the state or other authorizer and not the local district? For example, Atlanta Public Schools is the entity in this study that is guilty of three separate obstructionist tactics, but a board wishing to charter a school anywhere in Georgia can now go to the State Charter Schools Commission and get authorized under that body instead of having to deal with APS. The state’s commission might have a whole different maze of obstacles for chartership, or it could be easier, the applicant never knows until both avenues are investigated thoroughly. But again, even if the board gets chartered by the statewide authorizer, getting a building from APS to operate in the Atlanta metro area will be almost impossible.

In many cases, obstructions are not even ‘tactics’ so much as they are unfortunate realities of the statewide public education system. For instance, Los Angeles is guilty of three separate obstructionist tactics in this study, but freezing or delaying payments (#4) is not listed among them despite the state deferring payments to charter schools well beyond what is required by law. According to the California Charter Schools Association, approximately 59% of 2011-12 revenue was scheduled to be deferred at some point and 35% of state payments were scheduled for deferral into 2012-2013. California has also been criticized for not releasing charter school information to the district, a statewide obstructionist tactic to be sure, but aimed at the district instead of the charter community.

Regardless of which districts display obstructionist responses to charter growth and which tactics are used, the bright point of this study was that we saw a lot more Constructive behavior than Obstructive behavior in the districts with the most charter school influence (6%+ saturation) and the most challenging student demographic markets (60%+ FRL and minority).

Hopefully, this study can be expanded one day to include medium-sized districts, as well as the Constructive and Destructive responses and tactics of all authorizers, not just local districts. Authorization is a fickle beast, and just because district authorizers in one state are open to chartering schools doesn’t mean that districts in other states are, too. Nuances exist, which is why this study implies that Los Angeles Unified School District is more hostile to charters than other large districts, when in reality it had more than 300 charter schools last year, over half of which are under LAUSD and not the statewide authorizer.

(Chart is from study)

Warning: array_merge(): Expected parameter 1 to be an array, null given in /home/ameri317/public_html/wp-content/plugins/seo-facebook-comments/seofacebook.php on line 559

Warning: Invalid argument supplied for foreach() in /home/ameri317/public_html/wp-content/plugins/seo-facebook-comments/seofacebook.php on line 561